Unsolicited

April 27th, 2006In order to prevent shoplifting a huge neon colored sign right at the cash point of a local grocery reads

Please, show your bags UNSOLICITED!

Today, I had a bag with me. Heck, that made my head spin.

Welcome to the Club of Liars!

In order to prevent shoplifting a huge neon colored sign right at the cash point of a local grocery reads

Please, show your bags UNSOLICITED!

Today, I had a bag with me. Heck, that made my head spin.

Juliet Ernst suggests to have a ‘before you call’ list at hand that could help us to systematically rule out all the less significant possible causes before [we] panic or descend into real depressive funks.

This is a wonderful idea. So, I put on my list to make a list. Making lists sure is included in many people’s lists. Lists of people who like lists. That’s probably why there are recipes. Because life is complicated (which is a lie), and lists are simple (which is another one).

Like with good recipes we need more lists: Good lists, suitable lists, easy lists, short ones and long ones, comprehensive lists, serious, scientific lists, approved lists, experts’ lists, classifying and diminishing lists, and, of course, lists of lists, such as this one.

Eventually, do not forget to check your list of lists, and your schedules, your categories, registers, criteria, systems of divisions, rules for distinction; your catalogs and inventories; your principles, and

yourself.

What are the questions that we should ask?

What are the questions that we could possibly ask?

When I met Erwin Chargaff in his flat in New York, I felt like entering a new world, yet familiar. In his book “Kritik der Zukunft” he suggests that, for the time being, we declare our resignation from humankind.

Besides the fact that he says he did, I am to follow.

So here I am, outside.

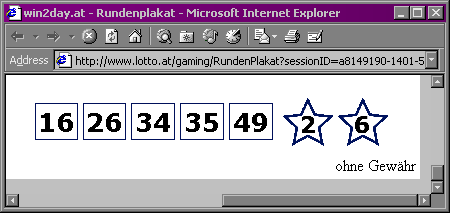

No responsibility is taken for the correctness of this information.

Once upon a time, there was a human ecologist. He came and said earnestly: Think globally, act locally!

And thus he did. He thought oh so globally, and he acted only locally. By chance, nobody knows him, but he lived happily ever after.

Who am I? — Of course, trivially I am I. But who says so? Who is I and who is I not? Can I trust this I?

Who am I? Who is me?

Am I the sum of my history, or am I more than the sum of it? Or less? I keep forgetting. Nature or nurture? Are my hopes and wishes part of me?

What about the collection of aches and pains that consume my body? How old am I? Old enough to kick my father’s butt? Am I ready to accept my rheumatic disorders? Or more? Where do I draw the line? On my birthday? When I die? Does death end my life, and me?

What have we forgotten about ourselves? There is this and that which I am proud of, what I believe in, and those I love. And there is everything else. I am the one to decide. So, it depends. I depend on me?

People keep asking: Who are you? — I’d like to answer honestly: I do not know. And I do, because there again is this I. I says about I that I does not know.

Maybe this is why trivial is not derived from a broad way but from three ways crossing at one point: The I that is me, the I that says I, and all that is not I.

Who said that?